[July 7, 2023]

AI Engineering and the Ethics of War

Jim Carlson is Shield AI’s General Counsel. Previously he was a software engineer, product manager, entrepreneur, and Marine Corps attack helicopter pilot having completed 100+ combat flights. He holds a JD, MBA, and BA from Stanford University.

My eight-year-old daughter’s favorite movie is Top Gun 2: Maverick. I’m not sure if her love for the film stems from a genuine interest, the fact that I stay up late to watch it with her whenever she wants, or knowing that her dad was a Marine attack pilot (of the infinitely cooler rotary-wing variety). Regardless, if I’ve lost any sleep over my decision to work at Shield AI, it’s over helping to obsolete my former profession and eliminate the possibility of her ever going Mach 2 with her hair on fire. Any regret is quelled, however, when I reflect on the two pilots we sent home early from my last deployment to Afghanistan – one to a trauma center and one in a body bag – and how their last missions could be fully automated.

The Realities of Ethical AI in Warfare vs Popular Culture

Hollywood and the media love to talk about ‘Killer Robots’ – a phrase that gathers views and clicks and something people can spend hours philosophizing over. The phrase captures popular and sincere concerns about the future of autonomous weapons. As an insider at Shield AI and a combat veteran, I have an optimistic perspective on the matter for two reasons.

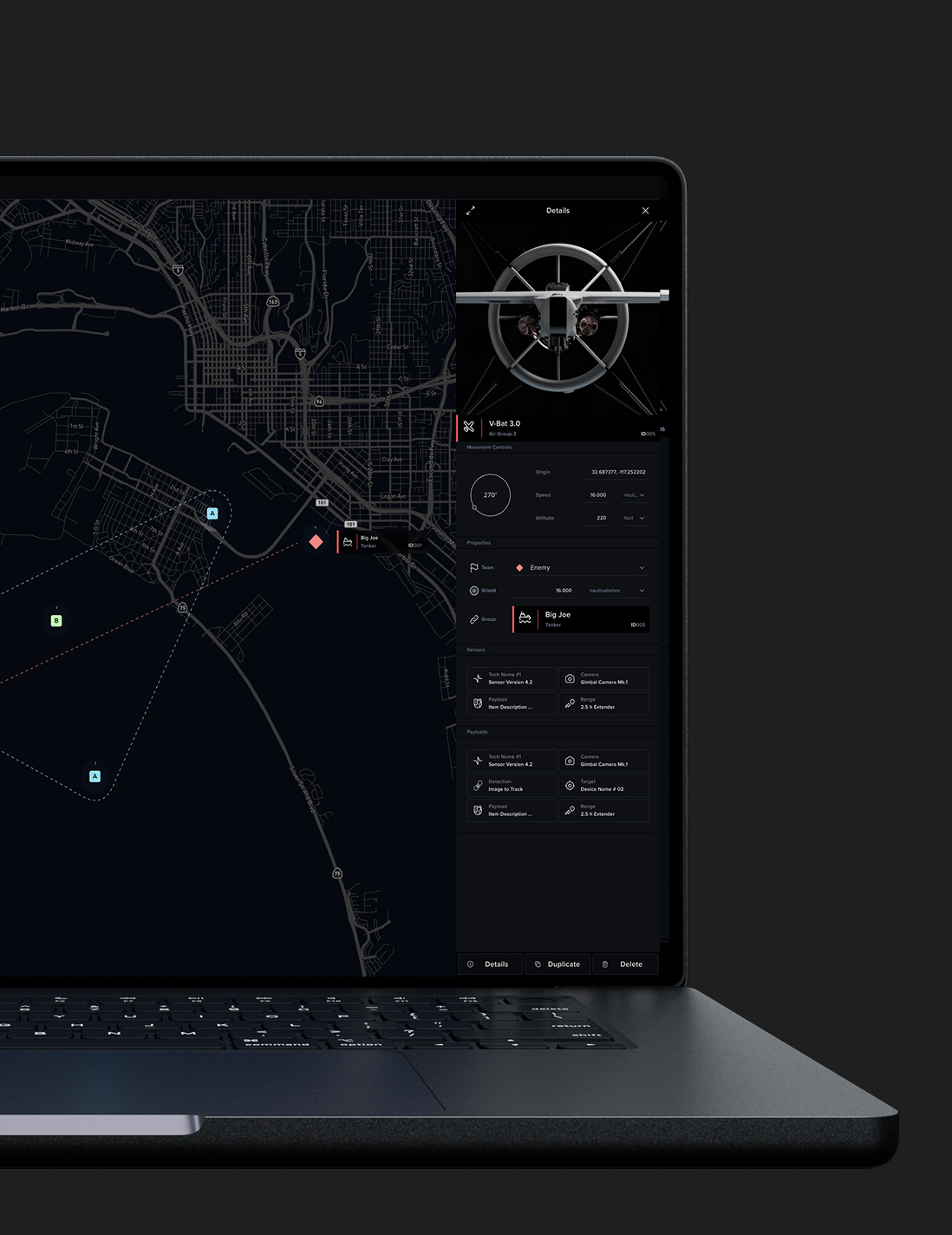

Firstly, while increased autonomy for unmanned aircraft is a national security priority, our focus is not on automating lethality, but rather on resilience – specifically resilience to communication and GPS jamming and denial. Current drones are not truly “unmanned” but rather “remotely piloted,” completely reliant on persistent data links for control and navigation. This model worked well for the U.S. on technologically asymmetrical battlefields where supremacy in the electromagnetic spectrum was assured. But it falls apart in conflicts against adversaries with jamming capabilities, as demonstrated in Ukraine. Thus, our work at Shield AI primarily aims to enable unmanned aircraft to carry out reconnaissance missions without the need for continuous human interaction or reference to a satellite constellation.

Secondly, I know that our work and the DoD’s policy on AI rest on a solid ethical foundation. The weaponization of autonomous systems (and automation of weapons systems) is inevitable. Indeed, it’s a historical fact: the Tomahawk Anti-Ship Missile (TASM), fielded in the 1980s and capable of searching for and engaging Soviet vessels, was arguably the first operational fully autonomous weapon. So, it is essential to have an ethical framework for the development and deployment of these systems. Fortunately, the DoD has been forward-looking in this regard with the publication of AI Ethical Principles and DoD Instruction 3000.09, “Autonomy in Weapon Systems.” This pragmatic policy includes the following requirements:

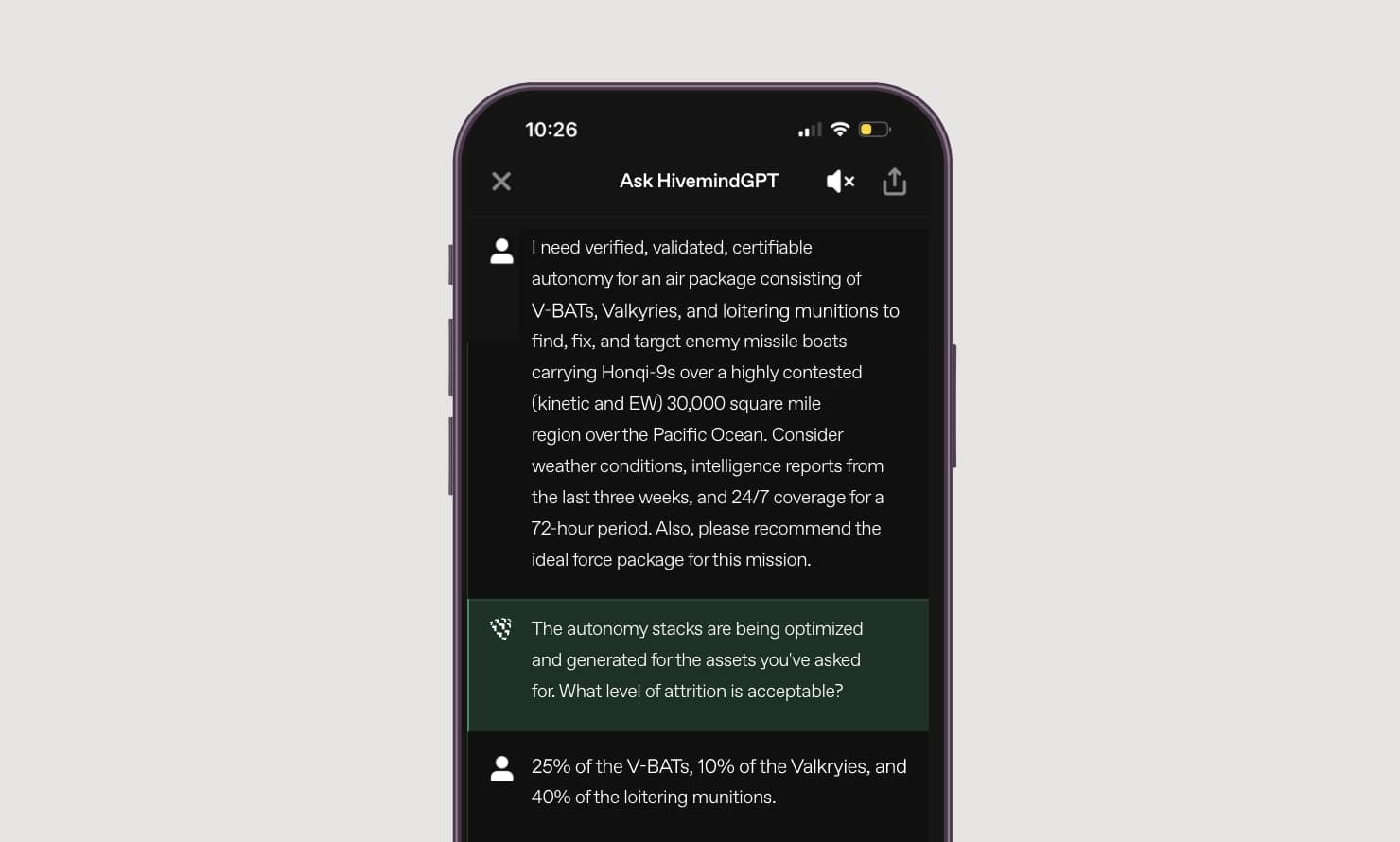

- Rigorous verification, validation, test, and evaluation

- Explainable technology and understandable human-machine interfaces

- Humans exercise appropriate levels of judgment over the use of force, with options to constrain engagements by time, geographic area, and other parameters

In other words, humans must be able to rely on, understand, and control their autonomous weapons. This is crucial because the ultimate ethical safeguard for autonomous weapons lies not in a new policy, but in the established law of war. Service members are taught these principles from the earliest days of their training: that each engagement must distinguish between combatants and civilians and that any risk of harm to civilians must be proportionate to the military necessity of the attack. These principles are operationalized through rules of engagement and standard procedures for the planning, approval, and control of fires. They govern the use of any weapon, autonomous or otherwise.

Human Judgment at the Core of Autonomy

As long as humans understand what a weapon system is capable of, how to constrain its operational envelope and its potential failures, they are in a position to employ it in accordance with the principles of the law of war. As a helicopter pilot, I considered these principles each time I launched a Hellfire missile. And while I didn’t consider the missile autonomous, there were instances where it had a “mind of its own.” In such cases, it missed in an unfortunate but predictable, probabilistic manner, consistent with prior validation and testing. I did my best to constrain its potential impact area through my choice of launch trajectory, in order to ensure the risk to non-combatants was minimal, and in all cases proportionate to the military necessity of the situation.

Autonomous weapons will likewise fail, occasionally and probabilistically, but a fortunate fact is that they will provide their human operators with more tools to constrain their potential impact. Today’s precision guided munitions can be instructed to guide themselves to a laser reflection or a GPS coordinate, but little else. However, an intelligent weapon system can receive more nuanced instructions – for example, to impact a specific location only if an enemy military vehicle is confirmed to be present and otherwise abort. While the algorithms enabling this discrimination will be imperfect, they will still represent additional tools for human operators to accomplish their mission while upholding the ethical demands of their profession. Wishing these algorithmic capabilities away in the name of ensuring more human control is akin to removing the laser guidance kit from a Hellfire missile and demanding that the pilot provide all the aiming – the operator’s toolkit is just poorer, and civilians are likely to pay the price.

The Inevitability of Progress and Its Impact on Warfare

New weapons technologies in the areas of deterrence and warfare are bound to face criticism and controversy as they advance. Yet there is a discernable trendline, from unguided bombs that were lucky to land within one thousand feet of their target in WWII to precision-guided munitions, that is leading to enhanced control over the effects of warfare. AI and autonomy promise to continue this progression by providing humans with greater influence while simultaneously reducing the number of humans required to be present on the battlefield. Our pursuit of AI and autonomy means that if my daughter chooses to serve her country to defend our Constitution and core values, she is more likely to command fleets of AI-piloted systems, guided by her ethical principles, than fly on dangerous missions like her dad.

Shield AI is focused on resilient autonomy and we are inspired by the potential of AI pilots to deter conflict entirely. It is the foundation of our mission to protect service members and civilians with intelligent systems. It is why we say the greatest victory requires no war.